African musical traits in African American music

Re: African musical traits in African American music

Here's another glaring fallacy among many. Too may to even waste time responding too.

"New World" (American) banjos are not descendants of the African stringed gourds in your non-dated photo.

That might fool 7th graders in your class as you can say "look, the bases are both round" and your students respond in unison "yeah".

And then you'll say, "and they're both wooden"... and your students exclaim "yeah".

And then you say " so the Americans copied the African inventors"...see?"

While the actual difference is the same as a donkey pulling a cart of straw and a Semi Truck loaded with semiconductors.

And that's why our schools are CRAP.

You have zero evidence that Europeans nor Americans fashioned or patterned their earliest banjos after the stringed gourd in the photo.

The original banjos the Europeans made could have possibly borrowed something from the far more sophisticated, round stringed instruments used in the middle-east. That's possible. Europeans nor Americans would never have made something as primitive as the stringed gourds you posted.

The American banjo used in earliest jazz music is a descendant of European and American stringed instruments.

The design, materials used, tuning system, detail, ornamentation are better in every way from the non-dated stringed gourds in your photo.

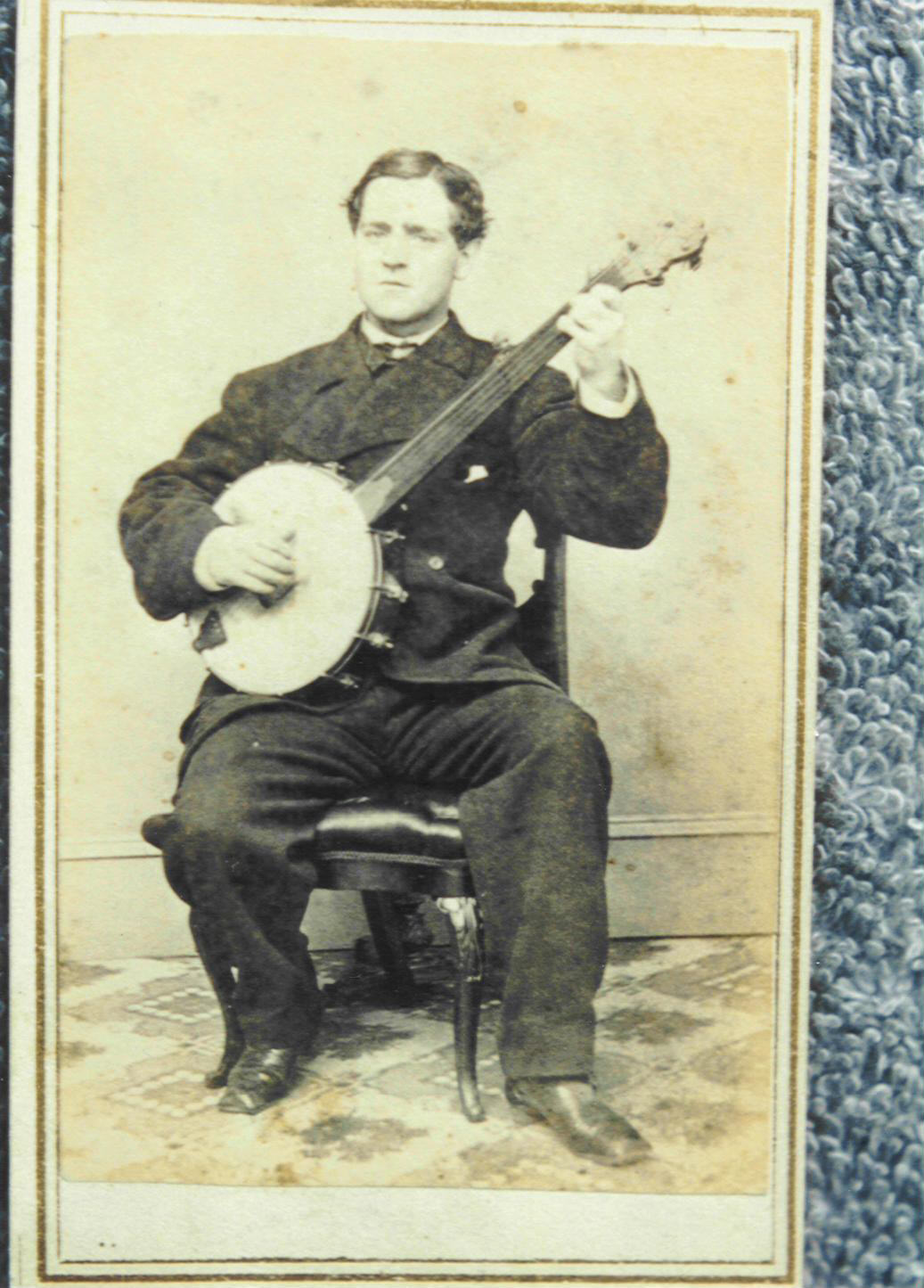

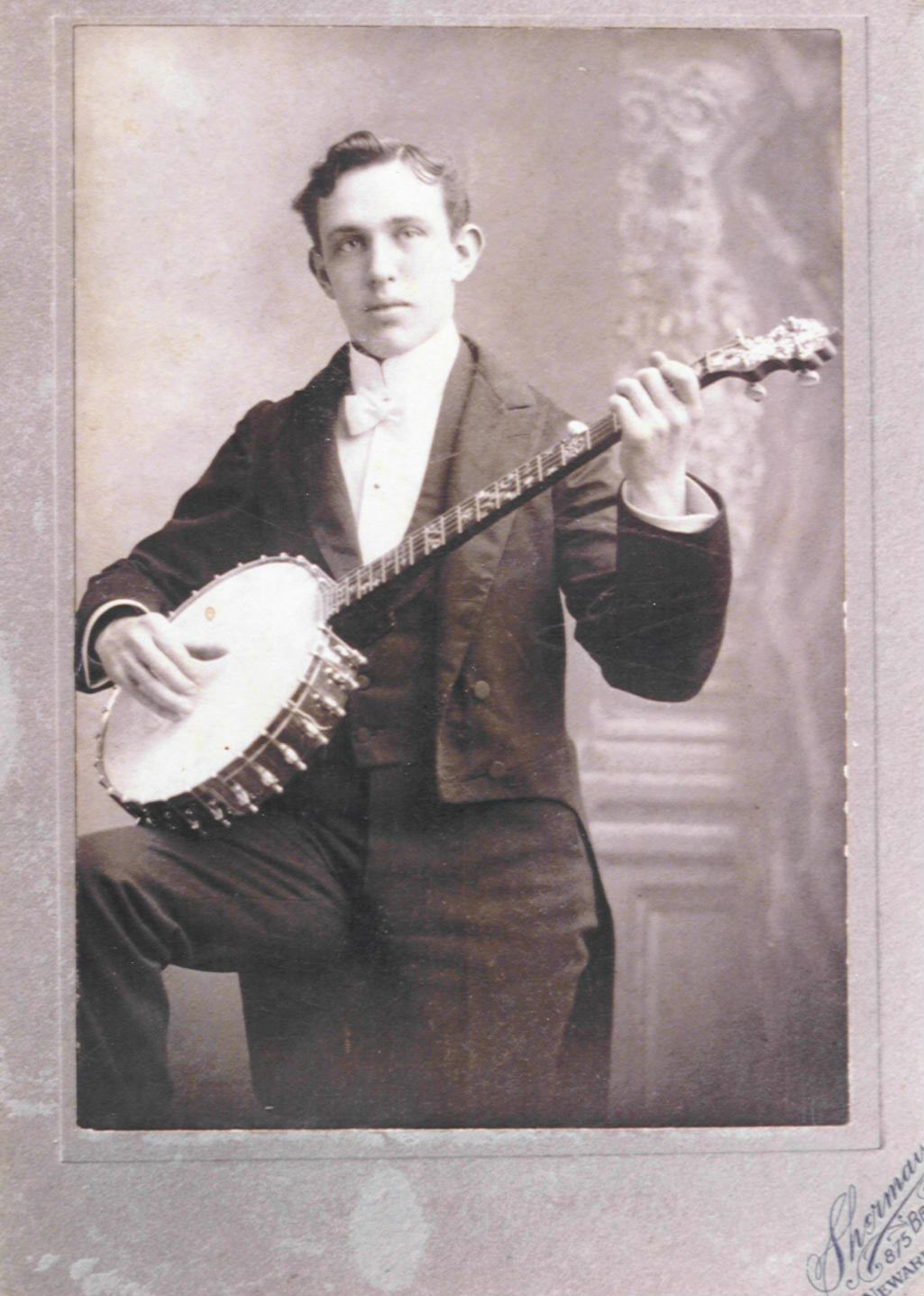

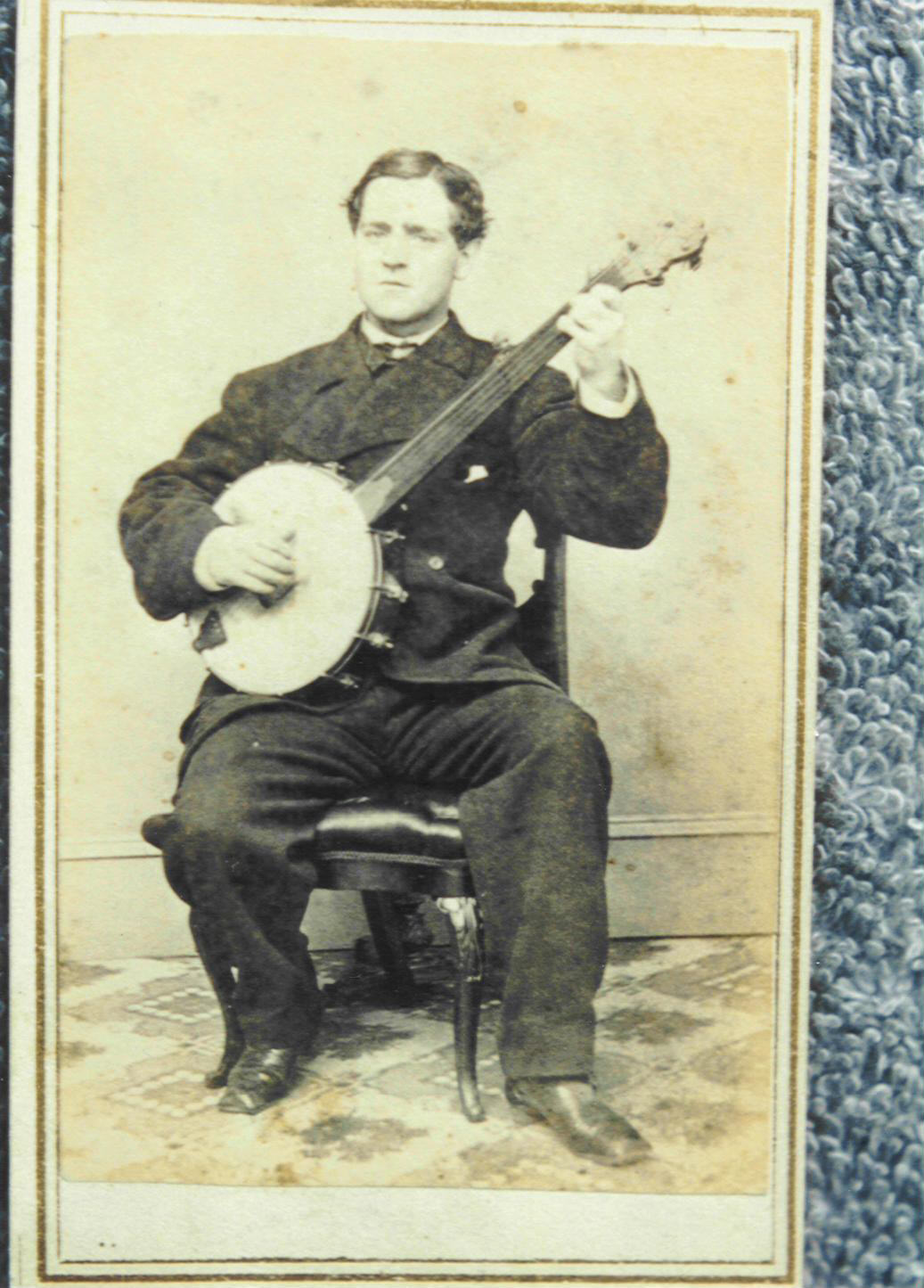

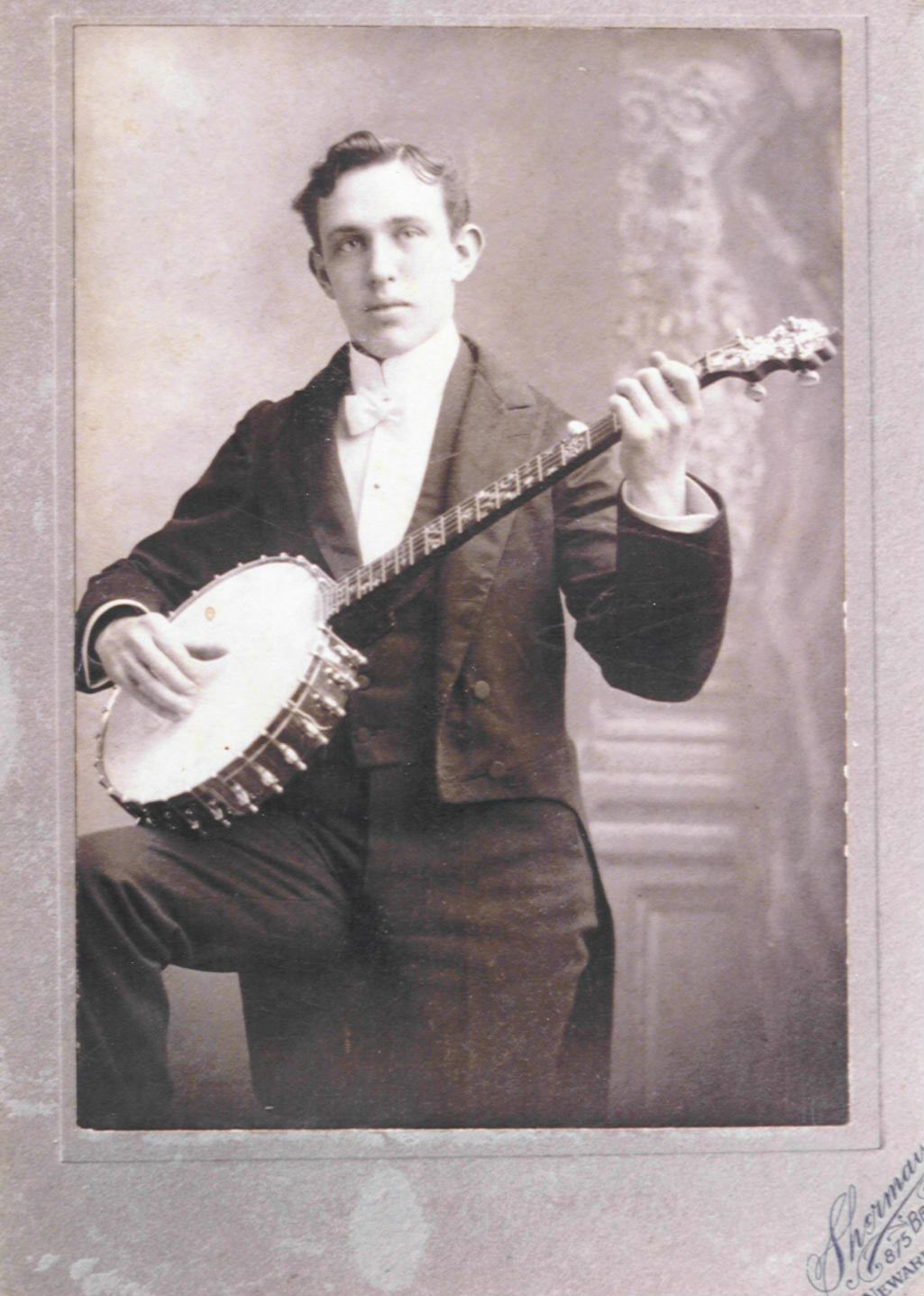

These are American banjos used in the creation of jazz.

They are infinitely more sophisticated and well-tuned, able to actually play all chords and melodies of European music.

The American banjo (1865)

(1900)

I won't waste another minute of time with this thread. It's a broke joke.

My only reason for responding is in the hope that this book will tell the truth and edit the lie about "some African instruments" being used in early jazz, there were none used. All of the instruments were American and European exclusively.

I did say that the African American banjo is a New World descendent of these Sudanic instruments.

"New World" (American) banjos are not descendants of the African stringed gourds in your non-dated photo.

That might fool 7th graders in your class as you can say "look, the bases are both round" and your students respond in unison "yeah".

And then you'll say, "and they're both wooden"... and your students exclaim "yeah".

And then you say " so the Americans copied the African inventors"...see?"

While the actual difference is the same as a donkey pulling a cart of straw and a Semi Truck loaded with semiconductors.

And that's why our schools are CRAP.

You have zero evidence that Europeans nor Americans fashioned or patterned their earliest banjos after the stringed gourd in the photo.

The original banjos the Europeans made could have possibly borrowed something from the far more sophisticated, round stringed instruments used in the middle-east. That's possible. Europeans nor Americans would never have made something as primitive as the stringed gourds you posted.

The American banjo used in earliest jazz music is a descendant of European and American stringed instruments.

The design, materials used, tuning system, detail, ornamentation are better in every way from the non-dated stringed gourds in your photo.

These are American banjos used in the creation of jazz.

They are infinitely more sophisticated and well-tuned, able to actually play all chords and melodies of European music.

The American banjo (1865)

(1900)

I won't waste another minute of time with this thread. It's a broke joke.

My only reason for responding is in the hope that this book will tell the truth and edit the lie about "some African instruments" being used in early jazz, there were none used. All of the instruments were American and European exclusively.

- congamyk

- Posts: 1142

- Joined: Thu Jul 05, 2001 6:59 pm

- Location: Vegas

Re: African musical traits in African American music

“Early African-American banjos consisted of a gourd or a carved wood body with a stretched skin head and usually little more than a stick for a neck”—Bill Evans, “A Brief History of the Banjo” Web.

Seeing is believing.

African American gourd banjo (1792)

African American gourd banjo (c. 1800)

African American carved wood body banjo (c. 1850-1875)

“The favorite and almost only instrument in use among the slaves then was banore; or as they pronounced the word, banjer. It’s body was a large hollow gourd, with a long handle attached to it, strung with catgut and played on with the finger”—Jonathan Boucher (1775).

“The five-stringed banjo is an American derivative of western and central Sudanic plucked lutes”—Kubik (1999: 16).

“The banjo’s history is a musical road map followed by American culture for over three centuries. It was born in the hands of African American slaves and later transformed by European Americans”—“Jubilee Gourd Banjo: The Genesis Instrument of American Music” banjopete.com.

Yes, the banjo is an African American instrument, which was transformed by European Americans. Notice the dates of the African Americans playing the gourd banjo above (1792, 1800). Compare those dates with the dates of the European Americans playing a more modern version of the banjo in the previous post (1865, 1900).

I suggest addressing the details Ricky's book in the thread New Conga Book. The name of this thread is African musical traits in African American music.

Seeing is believing.

African American gourd banjo (1792)

African American gourd banjo (c. 1800)

African American carved wood body banjo (c. 1850-1875)

“The favorite and almost only instrument in use among the slaves then was banore; or as they pronounced the word, banjer. It’s body was a large hollow gourd, with a long handle attached to it, strung with catgut and played on with the finger”—Jonathan Boucher (1775).

“The five-stringed banjo is an American derivative of western and central Sudanic plucked lutes”—Kubik (1999: 16).

“The banjo’s history is a musical road map followed by American culture for over three centuries. It was born in the hands of African American slaves and later transformed by European Americans”—“Jubilee Gourd Banjo: The Genesis Instrument of American Music” banjopete.com.

Yes, the banjo is an African American instrument, which was transformed by European Americans. Notice the dates of the African Americans playing the gourd banjo above (1792, 1800). Compare those dates with the dates of the European Americans playing a more modern version of the banjo in the previous post (1865, 1900).

I suggest addressing the details Ricky's book in the thread New Conga Book. The name of this thread is African musical traits in African American music.

-

davidpenalosa - Posts: 1151

- Joined: Sun May 29, 2005 6:44 pm

- Location: CA

Re: African musical traits in African American music

In my opinion, gourd banjo and banjo are two different instruments, the latter being non-african.

- shor

- Posts: 80

- Joined: Sun Sep 25, 2011 4:08 pm

- Location: Mexico city

Re: African musical traits in African American music

Guys,

check out these recordings: http://www.docarts.com/The-Hoddu-and-Xa ... negal.html .

This, to me, shows enough evidence of what this discussion is about; no comment necessary.

Thomas

check out these recordings: http://www.docarts.com/The-Hoddu-and-Xa ... negal.html .

This, to me, shows enough evidence of what this discussion is about; no comment necessary.

Thomas

- Thomas Altmann

- Posts: 906

- Joined: Sun Jul 02, 2006 12:25 pm

- Location: Hamburg

Re: African musical traits in African American music

The skin head in string instruments is found in various regions of the world.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yOlqjHC6llY

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yOlqjHC6llY

- shor

- Posts: 80

- Joined: Sun Sep 25, 2011 4:08 pm

- Location: Mexico city

Re: African musical traits in African American music

While in my previous post I was referring more to common traits in Afro-American Folk Blues and Sudanese Griot style, I may add to the discussion about the origin of the banjo the following, which is based on the book "Vorgeschichte des Jazz" ("Pre-History of Jazz") by the Austrian author Maximilian Hendler (Graz, 2008):

"A comparison with Sudanic lutes seems to suggest itself, but <the proof> of a direct derivation of the banjo must fail." (pg.31, my translation)

Hendler confirms that the history of the banjo is linked to the import of African slaves, but adverts us to the fact that Sudanese calabash lutes have round necks and strings of different lengths tied or clamped to different positions along the neck, much akin to primitive bow string harps, while the Afro-American banjo has a flattened neck with all of its strings tuned from one headstock on top of the neck. These features bear more resemblance with Iberian lutes and guitars, which in turn originated in Arabia, made there way to Spain and Portugal via North Africa, and were developed on the Iberian peninsula over 4-5 centuries. Hendler claims that "<the calabash or folk banjo> is a cross-breed of the Sudanese lutes <literally: 'sounds'> with round neck and clamp belt, whose different string length is part of its design, with the lutes <lit.: sounds> of the Portuguese whose similar forms can be found on their searoutes around Africa and on the India and Ceylon coasts."(pg.330) He places the origin of what he calls "substitutive lutes" at the point of encounter between Africans and Indians, respectively, and the Portuguese sailors and merchants.The banjo in particular, Hendler argues, "must be regarded as an instrument that could only be created under the specific conditions in the 'New World', but is nevertheless deeply rooted in Old-World lute traditions and can only be understood in a satifactory way if seen as such."(pg.45, my transl.) Until round-neck, clamp-belt gourd lutes are definitely traced down in America, the origin of crossover African-European lutes must be assumed somewhere along the West African coast (where the African-Portuguese "encounter" actually took place).

Hendler hints at the etymological kinship between the terms "banjo" and "bandolim" or "banjolim".

Hendler does not consider the possibility of a direct Arabian/Islamic influence on the creation of Sudanese lutes in Africa.

In closing, let me add that it is not my intention to convince anybody of something. There is no way of convincing someone who lacks an intuitive understanding of sheer evidence. To me, it is to be seen as a fact, that the Blues style, being a root component of Jazz, has its origin in the Griot tradition of the Senegambian belt (listen to the sound samples). Add to this the Caribbean rhythms that came to New Orleans from Haiti and Cuba and the turn-of-the-century popular song material from Europe, and we are already pretty close to the music that was to be called Jazz later on. Oh, I forgot the fife-and-drum tradition from Georgia and Mississippi, as documented on the CD "Traveling Through The Jungle" (Testament Records TCD 5017, 1971/1995). Interesting stuff.

Thomas

"A comparison with Sudanic lutes seems to suggest itself, but <the proof> of a direct derivation of the banjo must fail." (pg.31, my translation)

Hendler confirms that the history of the banjo is linked to the import of African slaves, but adverts us to the fact that Sudanese calabash lutes have round necks and strings of different lengths tied or clamped to different positions along the neck, much akin to primitive bow string harps, while the Afro-American banjo has a flattened neck with all of its strings tuned from one headstock on top of the neck. These features bear more resemblance with Iberian lutes and guitars, which in turn originated in Arabia, made there way to Spain and Portugal via North Africa, and were developed on the Iberian peninsula over 4-5 centuries. Hendler claims that "<the calabash or folk banjo> is a cross-breed of the Sudanese lutes <literally: 'sounds'> with round neck and clamp belt, whose different string length is part of its design, with the lutes <lit.: sounds> of the Portuguese whose similar forms can be found on their searoutes around Africa and on the India and Ceylon coasts."(pg.330) He places the origin of what he calls "substitutive lutes" at the point of encounter between Africans and Indians, respectively, and the Portuguese sailors and merchants.The banjo in particular, Hendler argues, "must be regarded as an instrument that could only be created under the specific conditions in the 'New World', but is nevertheless deeply rooted in Old-World lute traditions and can only be understood in a satifactory way if seen as such."(pg.45, my transl.) Until round-neck, clamp-belt gourd lutes are definitely traced down in America, the origin of crossover African-European lutes must be assumed somewhere along the West African coast (where the African-Portuguese "encounter" actually took place).

Hendler hints at the etymological kinship between the terms "banjo" and "bandolim" or "banjolim".

Hendler does not consider the possibility of a direct Arabian/Islamic influence on the creation of Sudanese lutes in Africa.

In closing, let me add that it is not my intention to convince anybody of something. There is no way of convincing someone who lacks an intuitive understanding of sheer evidence. To me, it is to be seen as a fact, that the Blues style, being a root component of Jazz, has its origin in the Griot tradition of the Senegambian belt (listen to the sound samples). Add to this the Caribbean rhythms that came to New Orleans from Haiti and Cuba and the turn-of-the-century popular song material from Europe, and we are already pretty close to the music that was to be called Jazz later on. Oh, I forgot the fife-and-drum tradition from Georgia and Mississippi, as documented on the CD "Traveling Through The Jungle" (Testament Records TCD 5017, 1971/1995). Interesting stuff.

Thomas

- Thomas Altmann

- Posts: 906

- Joined: Sun Jul 02, 2006 12:25 pm

- Location: Hamburg

Re: African musical traits in African American music

Very interesting article on the subject of this thread. You can read the whole article

at the link provided below.

http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-srv/st ... ofjazz.htm

The History of Jazz

By Ted Gioia

Chapter One: The Prehistory of Jazz

The Africanization of American Music

An elderly black man sits astride a large cylindrical drum. Using his fingers and the edge of his hand, he jabs repeatedly at the drum head--which is around a foot in diameter and probably made from an animal skin--evoking a throbbing pulsation with rapid, sharp strokes. A second drummer, holding his instrument between his knees, joins in, playing with the same staccato attack. A third black man, seated on the ground, plucks at a string instrument, the body of which is roughly fashioned from a calabash. Another calabash has been made into a drum, and a woman heats at it with two short sticks. One voice, then other voices join in. A dance of seeming contradictions accompanies this musical give-and-take, a moving hieroglyph that appears, on the one hand, informal and spontaneous yet, on closer inspection, ritualized and precise. It is a dance of massive proportions. A dense crowd of dark bodies forms into circular groups--perhaps five or six hundred individuals moving in time to the pulsations of the music, some swaying gently, others aggressively stomping their feet. A number of women in the group begin chanting.

The scene could be Africa. In fact, it is nineteenth-century New Orleans. Scattered firsthand accounts provide us with tantalizing details of these slave dances that took place in the open area then known as Congo Square--today Louis Armstrong Park stands on roughly the same ground--and there are perhaps no more intriguing documents in the history of African-American music. Benjamin Latrobe, the noted architect, witnessed one of these collective dances on February 21, 1819, and not only left a vivid written account of the event, but made several sketches of the instruments used. These drawings confirm that the musicians of Congo Square, circa 1819, were playing percussion and string instruments virtually identical to those characteristic of indigenous African music. Later documents add to our knowledge of the public slave dances in New Orleans but still leave many questions unanswered--some of which, in time, historical research may be able to cast light on while others may never be answered. One thing, however, is clear. Although we are inclined these days to view the intersection of European-American and African currents in music as a theoretical, almost metaphysical issue, these storied accounts of the Congo Square dances provide us with a real time and place, an actual transfer of totally African ritual to the native soil of the New World.

The dance itself, with its clusters of individuals moving in a circular pattern--the largest less than ten feet in diameter--harkens back to one of the most pervasive ritual ceremonies of Africa. This rotating, counterclockwise movement has been noted by ethnographers under many guises in various parts of the continent. In the Americas, the dance became known as the ring shout, and its appearance in New Orleans is only one of many documented instances. This tradition persisted well into the twentieth century: John and Alan Lomax recorded a ring shout in Louisiana for the Library of Congress in 1934 and attended others in Texas, Georgia, and the Bahamas. As late as the 1950s, jazz scholar Marshall Stearns witnessed unmistakable examples of the ring shout in South Carolina.

at the link provided below.

http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-srv/st ... ofjazz.htm

The History of Jazz

By Ted Gioia

Chapter One: The Prehistory of Jazz

The Africanization of American Music

An elderly black man sits astride a large cylindrical drum. Using his fingers and the edge of his hand, he jabs repeatedly at the drum head--which is around a foot in diameter and probably made from an animal skin--evoking a throbbing pulsation with rapid, sharp strokes. A second drummer, holding his instrument between his knees, joins in, playing with the same staccato attack. A third black man, seated on the ground, plucks at a string instrument, the body of which is roughly fashioned from a calabash. Another calabash has been made into a drum, and a woman heats at it with two short sticks. One voice, then other voices join in. A dance of seeming contradictions accompanies this musical give-and-take, a moving hieroglyph that appears, on the one hand, informal and spontaneous yet, on closer inspection, ritualized and precise. It is a dance of massive proportions. A dense crowd of dark bodies forms into circular groups--perhaps five or six hundred individuals moving in time to the pulsations of the music, some swaying gently, others aggressively stomping their feet. A number of women in the group begin chanting.

The scene could be Africa. In fact, it is nineteenth-century New Orleans. Scattered firsthand accounts provide us with tantalizing details of these slave dances that took place in the open area then known as Congo Square--today Louis Armstrong Park stands on roughly the same ground--and there are perhaps no more intriguing documents in the history of African-American music. Benjamin Latrobe, the noted architect, witnessed one of these collective dances on February 21, 1819, and not only left a vivid written account of the event, but made several sketches of the instruments used. These drawings confirm that the musicians of Congo Square, circa 1819, were playing percussion and string instruments virtually identical to those characteristic of indigenous African music. Later documents add to our knowledge of the public slave dances in New Orleans but still leave many questions unanswered--some of which, in time, historical research may be able to cast light on while others may never be answered. One thing, however, is clear. Although we are inclined these days to view the intersection of European-American and African currents in music as a theoretical, almost metaphysical issue, these storied accounts of the Congo Square dances provide us with a real time and place, an actual transfer of totally African ritual to the native soil of the New World.

The dance itself, with its clusters of individuals moving in a circular pattern--the largest less than ten feet in diameter--harkens back to one of the most pervasive ritual ceremonies of Africa. This rotating, counterclockwise movement has been noted by ethnographers under many guises in various parts of the continent. In the Americas, the dance became known as the ring shout, and its appearance in New Orleans is only one of many documented instances. This tradition persisted well into the twentieth century: John and Alan Lomax recorded a ring shout in Louisiana for the Library of Congress in 1934 and attended others in Texas, Georgia, and the Bahamas. As late as the 1950s, jazz scholar Marshall Stearns witnessed unmistakable examples of the ring shout in South Carolina.

- RitmoBoricua

- Posts: 1408

- Joined: Thu Feb 20, 2003 12:46 pm

Re: African musical traits in African American music

shor wrote:In my opinion, gourd banjo and banjo are two different instruments, the latter being non-african.

I think it's fair to say that many, if not most, original American music contains both European and African influences. Obviously European culture was dominant during the formation of American music, but just as obvious, the African American influence was disproportionally large. If one examines the history of African American, or Afro-Cuban music, it is possible to recognize influences from the "mother continents" waxing and waning. Therefore, it is a mistake to call the gourd bajo an African instrument, or the modern banjo a European instrument. It is an American instrument with both African and European influences, which has undergone a process of evolution.

"[Scott] Joplin was born in Texarkana, Texas, on November 24, 1868. His father, the former slave Jiles Joplin, had played the violin for house parties given by the local slave-owner in the days before the Emancipation Proclamation, while his mother, Florence Givens Joplin, sang and played the banjo. The latter instrument may have had a particular impact on Scott's musical sensibilities: the syncopated rhythms of nineteenth-century African-American banjo music are clear predecessors of the later piano rag style"—Ted Gioia, "The History of Jazz."

In closing, I acknowledge that Hendler and Kubik disagree on the issue of the banjo's Sudanic heritage. Thanks Thomas and RitmoBoricua for adding more information to this discussion.

-David

-

davidpenalosa - Posts: 1151

- Joined: Sun May 29, 2005 6:44 pm

- Location: CA

Re: African musical traits in African American music

I did a bit of internet search and came up with several informative sites, which focused on the banjo and not necessarily on African origins of it.

http://www.myspace.com/banjoroots/blog dates earliest documented American gourd banjos in late 1600’s.

The catalyst for the rapid transformation of the early American banjo to the modern banjo as we know it appears to be a man named Joel Walker Sweeney

http://www.drhorsehair.com/history.html

"Almost all ancient societies have had some sort of instrument with a vellum stretched over a hollow chamber with string vibrations creating tones, but most research indicates that our American banjo was developed from an instrument the Africans played here which they called banzas, banjars, banias, bangoes. Africans, brought to the new world in bondage and not allowed to play drums, started making their banjars and banzas from a calabash gourd. With the top one third of the gourd cut off, they would cover the hole with a ground hog hide, a goat skin, or sometimes a cat skin. These skins were usually secured with copper tacks or nails. The attached wooden neck was fretless and usually held three or four strings. Some of the first strings used were made of horsehair from the tail, twisted and waxed like a bowstring. Other strings used were made of gut, twine, a hemp fiber, or whatever else was available.

To Americans of European descent, the banjo was a creation of the Africans. The instrument was an oddity and was denied respectability. It was, in fact, a musical outcast, lowlier than the fiddle which many "righteous people" knew was from the devil. According to a 1969 article in "The Iron Worker", a trade publication of the Lynchburg Foundry Co. of Lynchburg, VA, a young man named Joel Walker Sweeney, of Appomattox Court House, VA, learned to play a four- string gourd banjo at age 13, from the black men working on his father's farm. He also learned to play the fiddle, sing, dance, and imitate animal sounds. Until this time, all performances on the banjo seem to have been from black players. Joel started traveling through central Virginia in the early 1830's, playing his five-string banjo, singing, reciting, and imitating animals during county court sessions. At this time he also started blackening his face with the ash of burnt cork as was popular for performers to do. As he played his homemade banjo, which was probably made of a gourd, his popularity and fame grew, so he enlarged his territory, playing in halls, taverns, schools and churches. These performances seem to be the first time that the banjo had been performed in a show, and the novelty of his act charmed both Negro and white spectators. He soon became a star in a circus which toured Virginia and North Carolina for several years. He eventually performed on his banjo in New York City, and even toured England, Scotland, and Ireland performing for Queen Victoria in 1843. Sweeney's introduction of the 5-string banjo to England led to the rise in popularity of the banjo there which has continued to the present"

http://bluegrassbanjo.org/banhist.html gives a bit more on Mr Sweeney

Joel Walker Sweeney of The Sweeney Minstrels, born 1810, was often credited with the invention of the short fifth string. Scholars know that this is not the case. A painting entitled The Old Plantation painted between 1777 and 1800 shows a black gourd banjo player with a banjo having the fifth string peg half-way up the neck. If Sweeney did add a fifth string to the banjo it was probably the lowest string, or fourth string by today's reckoning. This would parallel the development of the banjo elsewhere for example in England, where the tendency was to add more of the long strings with seven and ten strings being common. Sweeney was responsible for the spread of the banjo and probably contracted with a drum maker in Baltimore, William Boucher, to start producing banjos for public sales. These banjos are basically drums with necks attached. A number have survived and a couple of them are in the collections of the Smithsonian Institute in Washington.

Sweeney and his band “The Virginia Minstrels’” are a similar phenomena to the blackface players in the salon congas in Cuba in the early 20th century.

They make it permissible for white dominant culture to accept African culture as a part of the national heritage.

The African culture percolates below the surface of the dominant white culture; viewed with disdain,

and ignore-ance, yet utterly insuppressible and undeniable.

Eventually a catalyst occurs, and breaks the taboos which suddenly makes the African-ness of it (the banjo, the music) acceptable to the dominant white culture, and suddenly it is all the rage.

In the case of the banjo, even though it is documented to have existed in the Americas for 150+ years before his time, Sweeney’s promotion of it brought it to the attention of American and European instrument makers, who very rapidly refined and “westernized” it . As a sales item it took off like wildfire and was quickly assimilated into other American music styles.

Nationalizing Blackness by Robin D. Moore writes of the salon congas in Cuba: At the same time Africans in Cuba (there were still some alive in the early 20th century) were forbidden by law to play their drums, white Cubans were hiring them for private parties, and dressing up in blackface and acting out. The result of all this being that white dominant culture in Cuba began to accept the Africans contribution to Cuban’s music and culture as being valid, indeed indispensable

Elvis Presley is another catalyst for African-American culture and music, however in a much more direct way. He simply sang a black man’s song…like a black man might do it, with his 1954 recording of That's All Right, a cover of a song previously released by its composer, bluesman Arthur "Big Boy" Crudup, in 1946. Suddenly the taboos were broken and a generation of white teenagers had permission to shake their booties and shimmy like the blacks had always known how.

Presley was quoted as saying: "The colored folks been singing it and playing it just like I’m doin' now, man, for more years than I know. They played it like that in their shanties and in their juke joints and nobody paid it no mind 'til I goosed it up. I got it from them. Down in Tupelo, Mississippi, I used to hear old Arthur Crudup bang his box the way I do now and I said if I ever got to a place I could feel all old Arthur felt, I’d be a music man like nobody ever saw."

Little Richard said of Presley: "He was an integrator. Elvis was a blessing. They wouldn’t let black music through. He opened the door for black music."

Of all these instances, Robin D. Moore says it well in his book:

“White Cubans and white Americans also share an unfortunate tendency to appropriate black street culture while doing little or nothing to rectify existing social inequalities between the races. As Cristobal Diaz Ayala commented to me (Robin Moore) “We buy the product, but abhor the producer. Long live (jazz, rhythm and blues) the conga, the mulata, and fried plantains, but down with the negro!”

David, I hope I haven't diverged too much from the intended direction of your topic. I'll be quiet now.

http://www.myspace.com/banjoroots/blog dates earliest documented American gourd banjos in late 1600’s.

The catalyst for the rapid transformation of the early American banjo to the modern banjo as we know it appears to be a man named Joel Walker Sweeney

http://www.drhorsehair.com/history.html

"Almost all ancient societies have had some sort of instrument with a vellum stretched over a hollow chamber with string vibrations creating tones, but most research indicates that our American banjo was developed from an instrument the Africans played here which they called banzas, banjars, banias, bangoes. Africans, brought to the new world in bondage and not allowed to play drums, started making their banjars and banzas from a calabash gourd. With the top one third of the gourd cut off, they would cover the hole with a ground hog hide, a goat skin, or sometimes a cat skin. These skins were usually secured with copper tacks or nails. The attached wooden neck was fretless and usually held three or four strings. Some of the first strings used were made of horsehair from the tail, twisted and waxed like a bowstring. Other strings used were made of gut, twine, a hemp fiber, or whatever else was available.

To Americans of European descent, the banjo was a creation of the Africans. The instrument was an oddity and was denied respectability. It was, in fact, a musical outcast, lowlier than the fiddle which many "righteous people" knew was from the devil. According to a 1969 article in "The Iron Worker", a trade publication of the Lynchburg Foundry Co. of Lynchburg, VA, a young man named Joel Walker Sweeney, of Appomattox Court House, VA, learned to play a four- string gourd banjo at age 13, from the black men working on his father's farm. He also learned to play the fiddle, sing, dance, and imitate animal sounds. Until this time, all performances on the banjo seem to have been from black players. Joel started traveling through central Virginia in the early 1830's, playing his five-string banjo, singing, reciting, and imitating animals during county court sessions. At this time he also started blackening his face with the ash of burnt cork as was popular for performers to do. As he played his homemade banjo, which was probably made of a gourd, his popularity and fame grew, so he enlarged his territory, playing in halls, taverns, schools and churches. These performances seem to be the first time that the banjo had been performed in a show, and the novelty of his act charmed both Negro and white spectators. He soon became a star in a circus which toured Virginia and North Carolina for several years. He eventually performed on his banjo in New York City, and even toured England, Scotland, and Ireland performing for Queen Victoria in 1843. Sweeney's introduction of the 5-string banjo to England led to the rise in popularity of the banjo there which has continued to the present"

http://bluegrassbanjo.org/banhist.html gives a bit more on Mr Sweeney

Joel Walker Sweeney of The Sweeney Minstrels, born 1810, was often credited with the invention of the short fifth string. Scholars know that this is not the case. A painting entitled The Old Plantation painted between 1777 and 1800 shows a black gourd banjo player with a banjo having the fifth string peg half-way up the neck. If Sweeney did add a fifth string to the banjo it was probably the lowest string, or fourth string by today's reckoning. This would parallel the development of the banjo elsewhere for example in England, where the tendency was to add more of the long strings with seven and ten strings being common. Sweeney was responsible for the spread of the banjo and probably contracted with a drum maker in Baltimore, William Boucher, to start producing banjos for public sales. These banjos are basically drums with necks attached. A number have survived and a couple of them are in the collections of the Smithsonian Institute in Washington.

Sweeney and his band “The Virginia Minstrels’” are a similar phenomena to the blackface players in the salon congas in Cuba in the early 20th century.

They make it permissible for white dominant culture to accept African culture as a part of the national heritage.

The African culture percolates below the surface of the dominant white culture; viewed with disdain,

and ignore-ance, yet utterly insuppressible and undeniable.

Eventually a catalyst occurs, and breaks the taboos which suddenly makes the African-ness of it (the banjo, the music) acceptable to the dominant white culture, and suddenly it is all the rage.

In the case of the banjo, even though it is documented to have existed in the Americas for 150+ years before his time, Sweeney’s promotion of it brought it to the attention of American and European instrument makers, who very rapidly refined and “westernized” it . As a sales item it took off like wildfire and was quickly assimilated into other American music styles.

Nationalizing Blackness by Robin D. Moore writes of the salon congas in Cuba: At the same time Africans in Cuba (there were still some alive in the early 20th century) were forbidden by law to play their drums, white Cubans were hiring them for private parties, and dressing up in blackface and acting out. The result of all this being that white dominant culture in Cuba began to accept the Africans contribution to Cuban’s music and culture as being valid, indeed indispensable

Elvis Presley is another catalyst for African-American culture and music, however in a much more direct way. He simply sang a black man’s song…like a black man might do it, with his 1954 recording of That's All Right, a cover of a song previously released by its composer, bluesman Arthur "Big Boy" Crudup, in 1946. Suddenly the taboos were broken and a generation of white teenagers had permission to shake their booties and shimmy like the blacks had always known how.

Presley was quoted as saying: "The colored folks been singing it and playing it just like I’m doin' now, man, for more years than I know. They played it like that in their shanties and in their juke joints and nobody paid it no mind 'til I goosed it up. I got it from them. Down in Tupelo, Mississippi, I used to hear old Arthur Crudup bang his box the way I do now and I said if I ever got to a place I could feel all old Arthur felt, I’d be a music man like nobody ever saw."

Little Richard said of Presley: "He was an integrator. Elvis was a blessing. They wouldn’t let black music through. He opened the door for black music."

Of all these instances, Robin D. Moore says it well in his book:

“White Cubans and white Americans also share an unfortunate tendency to appropriate black street culture while doing little or nothing to rectify existing social inequalities between the races. As Cristobal Diaz Ayala commented to me (Robin Moore) “We buy the product, but abhor the producer. Long live (jazz, rhythm and blues) the conga, the mulata, and fried plantains, but down with the negro!”

David, I hope I haven't diverged too much from the intended direction of your topic. I'll be quiet now.

Last edited by Joseph on Wed Oct 05, 2011 6:40 pm, edited 2 times in total.

-

Joseph - Posts: 286

- Joined: Mon Jan 07, 2008 2:19 pm

- Location: St Augustine FL

Re: African musical traits in African American music

Joseph wrote:David, I hope I haven't diverged too much from the intended direction of your topic.

Not at all Joseph! The thread name is African musical traits in African American music and you are right in the middle of the sweet spot for this topic. Thanks for your informative post. One small thing, my friend Kevin Moore (author of the Tomas Cruz Conga method books, as well as the Beyond Salsa series), did not write Nationalizing Blackness. That was Robin Dale Moore. No biggie.

-David

-

davidpenalosa - Posts: 1151

- Joined: Sun May 29, 2005 6:44 pm

- Location: CA

Re: African musical traits in African American music

Oops!

Brain fart.

Thanks for the heads up.

Corrected.

Brain fart.

Thanks for the heads up.

Corrected.

-

Joseph - Posts: 286

- Joined: Mon Jan 07, 2008 2:19 pm

- Location: St Augustine FL

Re: African musical traits in African American music

RitmoBoricua wrote:Benjamin Latrobe, the noted architect, witnessed one of these collective dances on February 21, 1819

I'd forgotten about the journal of Benjamin Latrobe.

Google Books has it. Scroll down to p 180 for the Congo Square description.

Oh, to have experienced Congo Square in it's heyday.......

-

Joseph - Posts: 286

- Joined: Mon Jan 07, 2008 2:19 pm

- Location: St Augustine FL

Re: African musical traits in African American music

On a related topic; I am preparing to teach some Jr. High Schoolers about clave. Does anyone know of examples of recent hip hop or pop music that has either a tresillo or clave-based motif? I have a small collection of historic material, but I'd like to present something contemporary if possible. Thanks in advance.

-David

-David

-

davidpenalosa - Posts: 1151

- Joined: Sun May 29, 2005 6:44 pm

- Location: CA

Re: African musical traits in African American music

The DJ at the club where we have our Saturday night rumbas sometimes plays reggaeton between sets. When it is raining and I can't go outside between sets, sometimes I have to listen to it (earplugs in of course), and it does have a tresillo pattern against a downbeat. I wouldn't call it clave, the computer doesn't play it with any kind of feeling or anything, and I have trouble even mentioning it in a thread about African American music. I don't know any names of "artists" or specific records. In fact I really don't like it at all, don't tell anyone I recommended it to you, I have to protect my reputation you know...

- jorge

- Posts: 1128

- Joined: Thu Jun 15, 2006 3:47 am

- Location: Teaneck, NJ

Re: African musical traits in African American music

Thanks Jorge,

Reggaeton is a good suggestion.

(your secret is safe with me)

Reggaeton is a good suggestion.

(your secret is safe with me)

-

davidpenalosa - Posts: 1151

- Joined: Sun May 29, 2005 6:44 pm

- Location: CA

Who is online

Users browsing this forum: No registered users and 17 guests